The whole “men will try anything before doing therapy” line is, at this point, an accepted cultural truth. It’s everywhere—from memes to rage bait essays to representations in media—but for a long time, it felt like more a case of subtext as subtext rather than subtext as text. Honestly, even though I’ve been involved in trauma therapy and somatic practices for the past five years after my mental/physical health took a turn into crisis territory, I concede now that had I started some amount of therapeutical processing earlier, the crash might not have been as severe. Obviously, this is a universal human problem and not explicitly gender-based, but there’s definitely something in the way men bypass emotional stimuli that points towards deep levels of psychological repression. Let me be clear. I’m not comparing the “suffering” of men (especially cis heterosexual white men) to that of other minority groups existing under the strain of patriarchal culture. The last thing we need is another male writer conflating this issue and prattling on about how hard it is to be a man in this society. I’m simply observing that men are often encouraged to participate in stereotypes that ultimately undermine and damage their sense of identity.

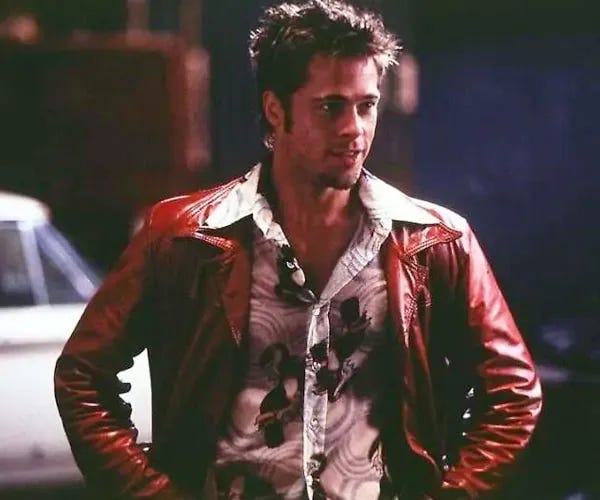

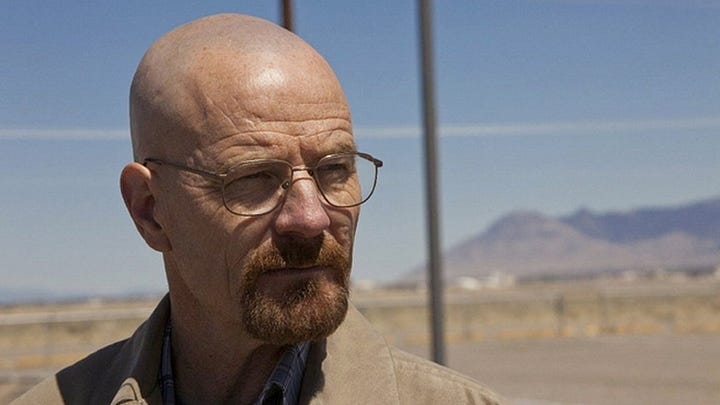

Of course, there are plenty of integrated men out there with tools for emotional regulation, right? The cynical part of me thinks all these supposedly healthy men are simply better at camouflaging their mental health struggles in order to save face in a culture which rewards hustle productivity over naked confessions of weakness, but what do I know? A number of films and TV shows have fixated on this particular phenomenon over time—1976’s Taxi Driver, 1999’s Fight Club, TV’s The Sopranos and Breaking Bad, just to name a few—but rarely has the term the male loneliness epidemic been used to describe the central characters of these projects. Travis Bickle was a misunderstood loner. Tyler Durden a manifestation of repressed male rage. Tony Soprano and Walter White are “anti-heroes” who take matters into their own hands. Even if audiences and critics acknowledged the potentially dangerous or unstable behaviour of these archetypes (Roger Ebert wrote an entire screed against Fight Club back in 1999), it does seem like it’s only in the last decade or so that we’ve really begun to reckon with the fact that men are inherently broken. Just look at any number of Letterboxd reviews for writer-director Andrew DeYoung’s feature debut, Friendship, and you’ll see a common theme of the “men will rather do X than go to therapy” variety. It’s a funny, if played out, response to a rather serious issue, and rather than go full farce, Friendship finds the middle line between satire and drama.

Tim Robison of sketch comedy sensation I Think You Should Leave fame stars as Craig Waterman, a sad suburban dad working for a tech company designing “habit forming” apps who is also trapped in a stagnant marriage with his ambitious wife, Tami (Kate Mara). They have a teenaged son, Steven (Jack Dylan Grazer) who seems to have an oddly intimate relationship with his mother (they kiss on the lips!) and a mostly detached one with his father. When Craig has a run in with weatherman/punk rock musician neighbor Austin Carmichael (Paul Rudd), his world opens up. Finally, he’s found a friend and someone to possibly fill his void of inner loneliness! Friendship has a setup not dissimilar to the 2009 bromance I Love You, Man (also starring Rudd), but this time the roles are reversed. In that one, Rudd was looking for a male best friend. Here, he’s the object of adoration—only Craig isn’t the lovable, Rush-loving stoner played by Jason Segel—but a deeply forlorn with the sour face of Tim Robinson.

What follows is a series of humiliations and social foibles in which Craig’s unmoored audacity for male companionship drives a rift between him and Austin (set off by a hangout with Austin’s friends that turns into a cringe-inducing display of passive aggressiveness). It’s a movie about ritual; how men redirect their emotions around tribalism—sports, games, drinking etc— and most potently, about how the inability for men to connect on a deeper level is like watching Craig bump his head against a closed glass door or stuff bars of soap into his mouth for being “a bad boy.”

Friendship isn’t a great film, but it is an important one because it manages to locate something true lurking at the heart of modern masculinity. I was often reminded of Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2002 masterpiece Punch Drunk Love, another film about a lonely man who occasionally lashes out in outbursts of violent rage. Both films use unconventional leads known for outrageous comedy and locates the inherent sadness that motivates their anger. Barry Egan (Adam Sandler) is someone cut off from human relationships—his only male friend seems to be his co-worker, wonderfully played by Luis Guzmán—and while Punch Drunk Love centers the male protagonist’s search for connection in the arms of a woman (Emily Watson), at his core, Barry is the poster manchild for the male loneliness epidemic.

The notion of upholding the monoculture is also a central theme in Friendship, given Craig’s brain-numbing job of app design and his need to remain spoiler free on the latest Marvel movie (“Haven’t had a chance to see it yet because the newest Marvel is nuts. Like apparently it’s actually making people go crazy…” ). There’s a banality to Craig’s daily life that draws out uncomfortable laughs, but what struck me most beyond the film’s cringe comedy scenarios is Craig’s incessant need for male human contact. I found myself relating to him and then feeling ashamed of identifying with such a pathetic loser. Robinson’s performance is key because despite how neurotic, awkward, and annoying Craig can be, there’s something deeply human about his desire for connection. It’s so blatant as to be alarming, but aren’t we all simply masking our need to be admired, loved, and accepted? Rudd’s swaggering weatherman might initially appear to be the middle-age alpha ideal, but his existential crisis is simply less obvious (complete with a meta gag that plays off Rudd’s agelessness) that further cements the film’s dissection of male malaise. Perhaps the movie’s defining scene involves Craig dragging over his newly bought drum set to Austin’s doorstep in hopes of engaging in a jam session, only to be ruthlessly rejected. “I don’t want to continue with this friendship,” Austin concludes, to which Craig responds by pointing out that he was accepted into the fold much too quickly. His primal confession of doing one weird thing to alter their dynamic is instantly relatable. Who hasn’t second-guessed themselves socially after noticing the vibes shift in the room? How many of us, like Craig, have felt the crippling insecurity of being ushered into the tribe only to be cast out after some seemingly innocent social faux pas?

DeYoung’s film is episodic and shaggy, filled with stressful social situations which ratchet up slowly until Craig eventually explodes in anger (his rants are pitched very similarly to the moments where Sandler loses his cool in Punch Drunk Love). Craig’s outbursts are often uncomfortably funny, but we understand where they are coming from. The idea of being judged, sharing too much/not enough, or just coming off weird to others is a universal fear, but straight men are even less adept at navigating these kinds of interactions. While never explicitly giving us background detail or outlining Craig’s specific issues, Friendship simply presents the reality of how loaded first time interactions between men can be.

The film is ultimately coy about how earnest its intentions are at interrogating these ideas, using its anti-comedy roots to toy with our expectations regarding the seriousness of the underlining themes. Are we laughing at Craig for his ineptitude, or is our laughter somehow reflective of an inner fear that we, too, are suppressing a longing for interrelatedness? In the end, Craig Waterman isn’t the hero or villain of his own story, but merely a lonely soul reaching out for a life raft on the turbulent tides of the male loneliness epidemic.

*Friendship is currently in theatrical release and available on VOD platforms June 17